I – Towards the management of diversity in the classroom

I.1 – This handbook

I.2 – The DIVERSE project

I.3 – The current challenges

I.4 – Opening up the classroom

II – Drama in Education

II.1 – Introduction to the theory

II.2 – Description of the method

II.3 – Three lesson plans

II.4 – Some more tools

II.5 – Resources

III – Digital storytelling

III.1 – Introduction to theory

III.2 – Description of the method

III.2.1 – Aims of the method

III.2.2 – Application across the curriculum

III.2.3 – Resources and technology requirements

III.2.4 – Creating characters (sprites) and backgrounds (backdrops)

III.2.5 – Moving the characters

III.2.6 – Creating a dialogue between two characters

III.2.7 – Creating a story (a sequence of scenes)

III.2.8 – Possible issues

III.2.9 – Making the story collaborative

III.2.10 – Organization. Different collaborative options

III.3 – Three lesson plans

III.4 – Some more tools

III.5 – Resources

IV – Folktales

IV.1 – Introduction to theory

IV.2 – Description of the method

IV.3 – Two lesson plans

IV.4 – Some more tools

IV.5 – Resources

V – References

III.2.9 - Making the story collaborative

How do we all decide a general story/topic?

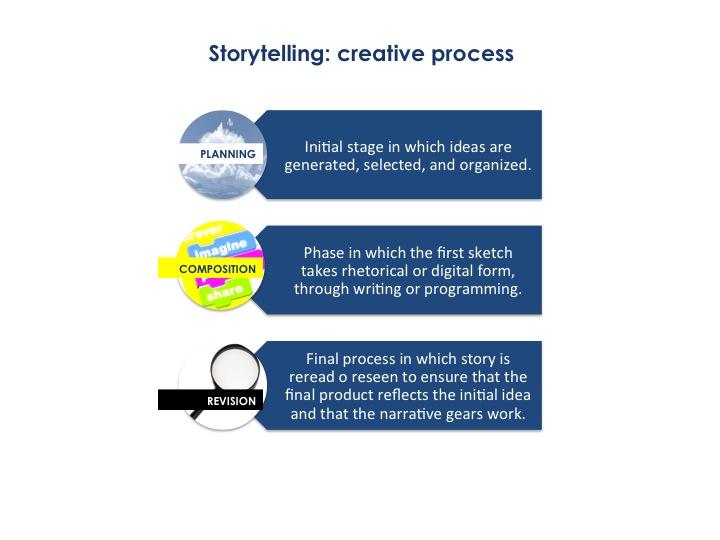

In the process of creating a story, the teacher must dedicate some time to each of the phases of planning, composition and revision.

In planning, ideas are generated, selected and organized, and the story gets born. Composition is the phase in which planning takes rhetorical or digital form, through linear writing or programming. Revision is the final process in which creation is reviewed to ensure that the final product reflects the initial idea and that the narrative gears work (no likelihood issues, undeveloped characters, etc.).

This section focuses on planning: the stage where the creative process must take place, the invention of the story. This phase cannot be reduced or omitted: it needs time and resources for ideas to take shape; that will enable students to focus on the demands and resources of digital storytelling during the following stages. In planning the teacher must make resources and strategies available to students so that ideas flow. And these strategies must be diversified over the year, in each activity that is done. Here are some suggestions:

1. Document yourself: An intense story can emerge from reality. Sometimes we just have to read the newspaper or listen to the news to find great plots. For instance, the event sections can be used to build short stories where chance or bad luck have great importance; history books can be the basis of informative storytelling; in-depth interviews can help us to build short biographies…

2. Documenting yourself to relive and empathize: There is very poignant news (that should hit us, and sometimes they don’t) that can become a literary plot if we explain it with proper resources, other than journalism, or if we change the perspective. For example, a headline like “Detained 11 occupants of a boat arrived yesterday on the coast of Ibiza” can become a story or a scene if we give names and faces to these eleven people (or at least to three of them), we think what has led them to get on board, imagine if they knew each other or not before starting the journey and what kind of relationship they settled while they were sailing between the waves and fear.

3. Versioning: Remaking or adapting classic stories, myths, fairy tales, from new perspectives, other points of views…

4. Cocreating: Develop a story together with other students, sharing ideas and different points of view; making ideas grow through interaction and dialogue among participants, using the brainstorming technique.

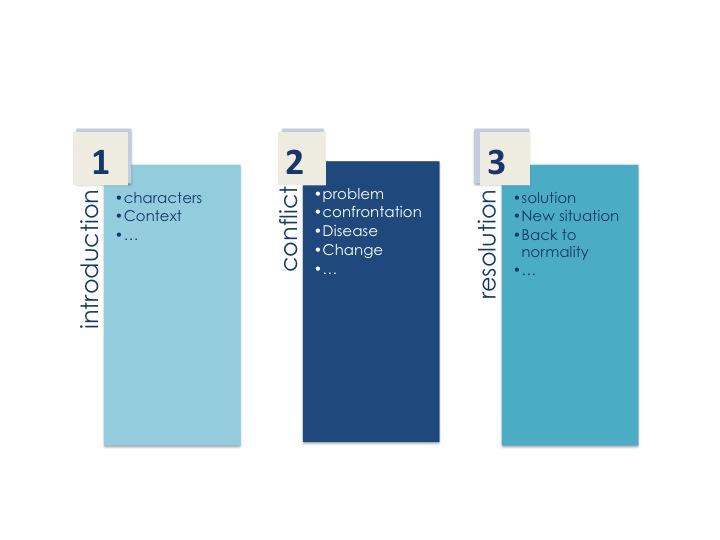

The aim of the teacher must be to ensure that students are able to turn good ideas into good stories: for this, it is necessary to help them to hybridise all the contributions, to sew all the threads. Students also need to keep in mind that most stories have an introduction, a conflict and a resolution. Students can decide not to follow this narrative scheme and choose other options: to make a scene, a portrait… where a conflict or a resolution might not be necessary. But teachers have to make sure that students make the choice accurately, and they don’t end up constructing incomplete or incomprehensible stories.

If, for example, students create a large number of characters, the teacher should ask them what role they will play in the story; it is necessary to integrate them in the argument, to give them a mission, if any of them definitely does not have its own profile the teacher must suggest that he/she can be elided or transformed. If some of the conflicts suggested at the introduction remained open at the resolution, they have not been mentioned again, teacher must remind the students that they should be confronted.

Cocreation

Cocreation through brainstorming is a granted option, since conversation fosters creativity: an idea brings a new idea in an iterative process. But sometimes a spark is needed to focus the fantasy and the creativity of students towards new scenarios, new conflicts or new characters, to help them to be original, innovative. In these cases, Grammatica della fantasia by Gianni Rodari, can be very useful. This work, translated into almost all European languages, is today a classic in the didactics of creativity: it offers about forty techniques explained in detail and with examples to spur fantasy, so that children and adolescents are able to generate new disruptive stories. Rodari often resorts to strangeness, which consists in breaking logical associations of thought and generating new connections, placing the student in unusual situations. This is achieved by creating unusual pairs, displacing objects or characters out of their usual scope, distorting fundamental elements of our daily lives, and so on. Here are some examples of Rodari’s techniques:

Fantastic binomial: if we ask children to create a story using the words cat and dog, the two animals would fight and the plot probably won’t surprise us? What if, instead, the protagonists have to build the stories using the words cat and toaster? Or dog and razor? Students will be compelled to settle new connections. Rodari proposes that we choose two words at random, which are not usually combined, and take them as a starting point. This will surely evoke disruptive arguments.

What if …? The fantastic hypothesis: if we change a single feature of our daily lives, everything is shaken and a whole series of things begin to happen: this could be the beginning of great stories. What if our whole city became monochrome (red, for instance)? What if there were no more doors anywhere? With small initial pretexts like these, teachers can enhance children’s creativity and encourage them to explore new paths.

From here, it will be very important the interaction (brainstorming) between students in order to grow and develop the story: this way, first ideas are developed, grow, are enriched, nuanced with everyone’s contributions.

How do we create a modern version of a classic story?

Another source of good stories are the classic fairy tales and myths: we can take advantage of their powerful characters and narratives and rewrite them using different strategies. Rodari develops different options in the book quoted. We name some below…

Replace an old myth or character: locate him/her, for instance, in the 21st century, in our society. We can adapt or remake classic stories from a gender perspective or write them from an intercultural perspective. How would female characters react nowadays? What would be the point of view of the story if it were told by the bad characters, the losers, the beasts?

Continue the story: make a second part of it. What would happen afterwards? Let’s take advantage of strong and well-defined characters to imagine new adventures.

Change the focus: Choose a secondary character and make him become the main character. Give voice to the characters who have less.

To make these transformations, it is necessary to have a deep comprehension of the classic fairy tales or myths, to come to grasp their basic essence in order to give them a new shape. This requires a dialogic reading session, in which students will share their ideas about the selected text (myth or tale) and discuss them to delve into it; from here on, classic stories can be wrapped in new ways and retain their essence.

Here are two examples of how to transform some passages from the Odyssey into new stories:

> Polyphemus, the one-eyed monster who catches Ulysses and his men, and from whom only he manages to escape, is truly fearsome, he embodies fear since he is strange, tall, strong and cruel. What would an urban Polyphemus look like in the 21st century? What attributes should we give him to make him seem fearful and unsettling?

> Penelope waits twenty years for Ulysses without having news from him: she is a submissive and faithful woman. This behaviour is the best proof of your love. Do you think that would have been the case today? What would Penelope have done nowadays to show her love for Ulysses?